The project

A sweeping metamorphosis affects the representation of power in post-Renaissance Europe. Now the king goes on stage, as he plays the ancient hero (e.g. Caesar, Hercules), the pagan deity (e.g. Jupiter, Apollo) or even the Saviour, by merging the body of Christ with his body politic during religious processions. The king appropriates mythological and literary characters to exploit the force of their cultural legacy, and, in so doing, his dramatic persona - i.e. his figure as presented to and perceived by others - comes to be the focus of a large propaganda campaign.

Ferdinand III of Hapsburg, for instance, writes and publishes a collection of Italian poems to magnify his own devotion, while Louis XIII of France dances court ballets in the shoes of ancient gods and epic commanders. The same goes for Louis XIV’s portraits and mythological praises. Apollo does not stand for the king; Apollo is the king, as the former is represented with the latter’s features (e.g. hair, moustache). Thus, a direct link connecting the king and his subjects is established, as shown by the extensive expansion of the cult of the monarchy in Baroque arts, literature, and court etiquette.

However, some major players on the European stage, like the Republic of Genoa and Venice or the Dutch Republic, have no king to celebrate. Their figureheads, the doge and the stadtholder, have neither a divine right to invoke nor an absolutist persona to stage. They do not dress in the over-the-top mythological disguises worn by the king, because their bodies cannot fit the body politic of the state. In this respect, early modern Republics seem to have little to do with the political ritualization of absolute monarchies.

Yet, are we sure that Republican culture and civic ritual are not affected by the metamorphosis shaping the image of kingship during the so-called Ancien Régime? Republics eschewed any vestiges of monarchy to state their independence; still, they could not but refer to the same historical framework, marked by spectacular displays of ceremonial pomp, magnificent and clockwork rituals, and centralizing power.

The RISK project addresses this issue. By comparing the representation of kingship and the staging of the Republican state, RISK does not merely expand the area of inquiry - from absolute monarchy to seventeenth-century Republicanism - but it rather opens up a whole set of new questions. To what extent does the absolutist framework influence the display of Republican ideals such as freedom, equality, and the common good? How may the rhetorical devices of baroque culture extoll a power that does not apply to someone (the king) but rather to something (the Republic and Republican virtues)?

In order to answer these questions, RISK studies and compares several Republican states. The goal is to define their similarities and differences in approaching this new-fangled representation of power. For this purpose, RISK provides the first comprehensive overview of the Republican displays of state power in Europe from the late sixteenth to the early eighteenth century. Five case studies are considered: the Italian city-states that maintained their independence throughout this timeframe (Venice, Genoa, Lucca), the Republic of Ragusa (today in southernmost Croatia) and the Dutch Republic. Therefore, RISK covers a wide range of diverse political traditions.

In Genoa, Lucca and Ragusa, for instance, Republican authority is put to the test by foreign allies and power relationships: Genoa is in the Spanish sphere of influence at least from 1557; Lucca has acknowledged Imperial authority since 1521; and Ragusa is a tributary of the sultan from 1526. Venice and Amsterdam are stronger political subjects; yet, they also have to confront the Europe of absolute monarchies, in which any Republic needs to protect its independence and justify its very existence. The new celebratory patterns that RISK investigates are intended precisely for this purpose.

It should be noted that the staging of early modern power is a comprehensive audio-visual expression, pivoting on several media. Writing merges not only with music, visual arts, and performance, but also with technological devices such as smoke, fountains, and fireworks; hence, a true multimedia experience is created. As RISK examines Republican pageantry and encomiastic production in its multimedia appearance, a multidisciplinary corpus of sources is taken into account.

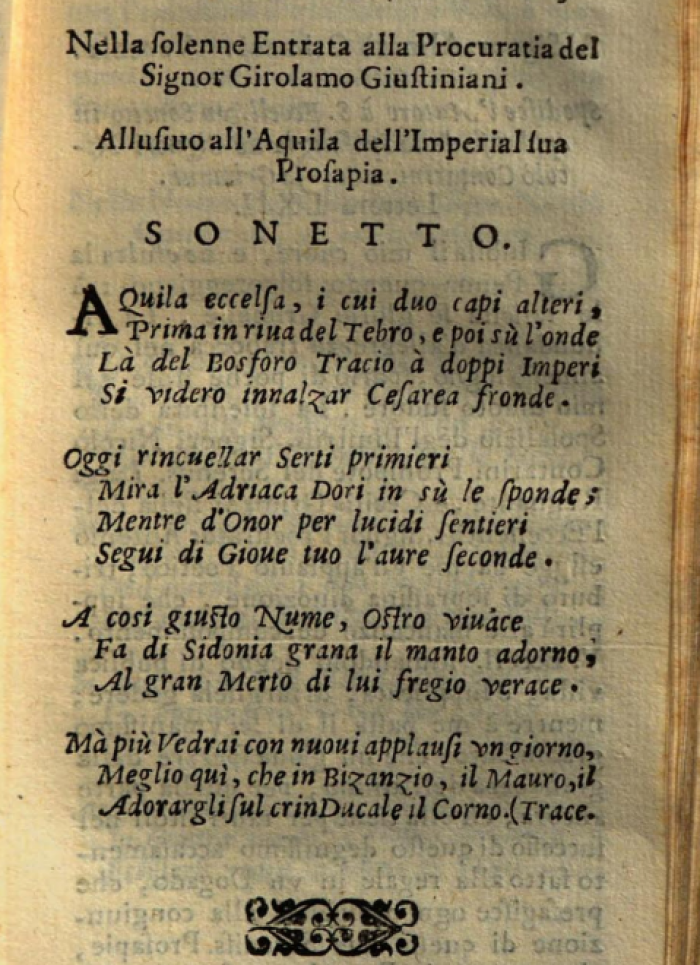

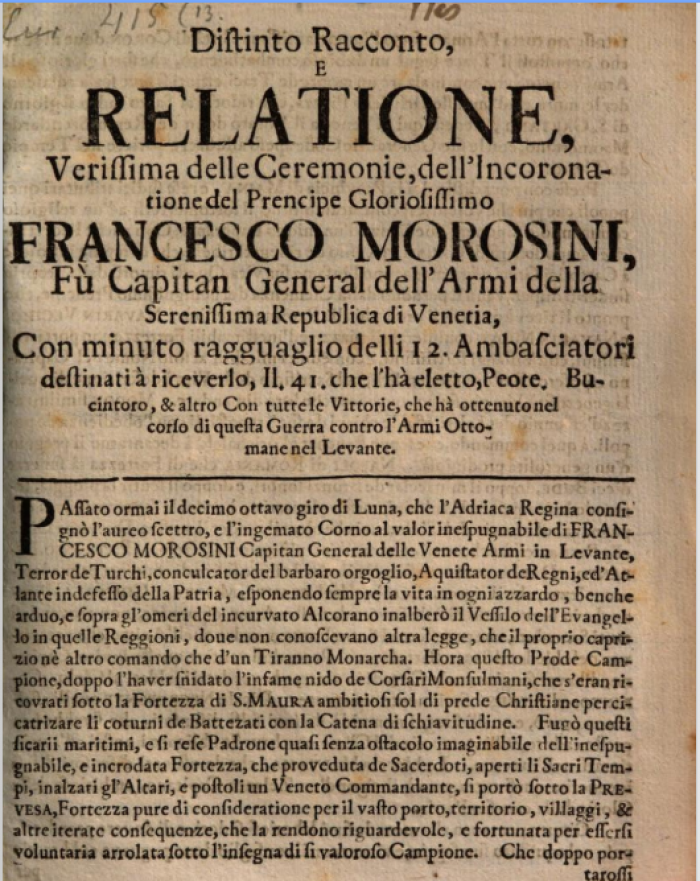

- Praising texts celebrating Republican offices and values, in both verse and prose: laudatory treatises, panegyrics dedicated to powerful citizens, civic orations publicly declaimed on special occasions (such as the coronation of the doge in Genoa and Venice) and then published in what we would call an instant book.

- Paintings and engravings displaying civic rituals (e.g. entries, elections, regattas), or portraying mythological prosopopoeias of the Republic.

- Festival books and written accounts of public ceremonies, describing in detail (often with the aid of emblems and engravings) the triumph performed after a victorious campaign, the processions for a religious event, or the festivities held after an election.

The analysis of this broad corpus of sources allows us to develop new interpretative frameworks, by connecting, combining and interpolating different disciplines and scientific approaches. Indeed, the main research strands regarding early modern republicanism and the representation of absolute power have never come into contact. This is mainly due to the disciplinary fields in which such studies have been conducted, as each discipline (e.g. literary studies, cultural, intellectual, and art history) applies its own categories to a specific object (e.g. respectively court literature, civic ritual, open sphere, and early modern festival). By bringing together what has been separated, RISK aims to undermine the current scientific paradigms and put forward more ambitious and across-the-board models.

The Ancien Régime has been generally perceived to have been marked by the rise of a unique political model, i.e. the absolute monarchy. RISK studies an alternative genealogy for Europe’s identity. Indeed, republicanism offers a repertoire of images and concepts that embodies a different mode of thinking about the state. This legacy allows us to challenge the received idea of a Janus-faced early modern culture, where a series of binary oppositions would supposedly herald the transition towards modern democracy (monarchy vs. republic, absolutism vs. liberty, propaganda vs. public sphere). RISK undermines these juxtapositions, as it highlights the richness and the plurality of our cultural heritage.